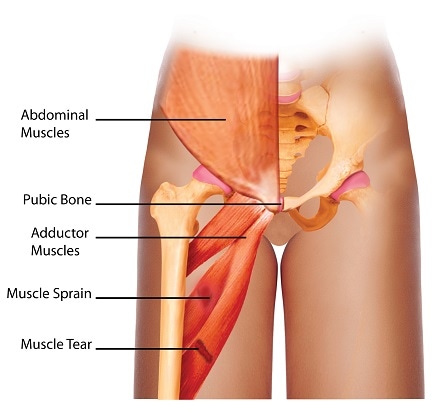

Groin strain accounts for 2 to 5 percent of all sports-related injuries and is more prevalent in sports such as fencing, high jump, hurdles, handball, ice hockey, cricket, calisthenics, and football. Although it has a low incidence rate, groin pain is frustrating to diagnose even for experienced physicians, due to the complex anatomy of the area and the possibility that more than one injury may exist; up to 30% of cases remain uncertain because of these factors.

Groin or adductor strain, specifically, is a common sports injury, especially in soccer; these players are particularly susceptible to groin injuries, with incidence rates being as high as 18%, and 62% of these injuries being diagnosed as the groin strain. This type of injury usually occurs at the muscle-tendon junction, which is the weakest point in this unit, or where the tendons attach to the bone.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of a groin strain are:

- Pain on palpation

- Pain during adduction against resistance, for example, the use of a resistance band

Causes/Risk Factors

- A previous groin strain. This is a major risk factor, as recurrent rates have been found to be as high as 32%; in other words, 1 in every 3 patients that had a previous groin strain will have a recurrent injury. This finding was supported by another article that found that Swedish athletes that had a previous groin, hamstring or knee injury were 2 to 3 times more likely to have another similar injury in the next season.

- The flexibility of the adductor muscles. This factor is still controversial, as studies have found conflicting results. One study that looked at soccer players found that reduced hip adductor flexibility was positively associated with increased incidence of adductor strains. Another study which looked at ice hockey players, however, did not see this association.

- The strength of the adductor muscles. This factor is also uncertain, as there has been conflicting data in the literature. On the one hand, one study did see a relationship between lower strength in adductor muscles and increased incidence in groin strain, but another study did not find this relationship. Both studies investigated the ice hockey athletic population.

- Practice during off-season. One study found that those that trained during the off-season were less likely to sustain a groin strain.

Diagnosis

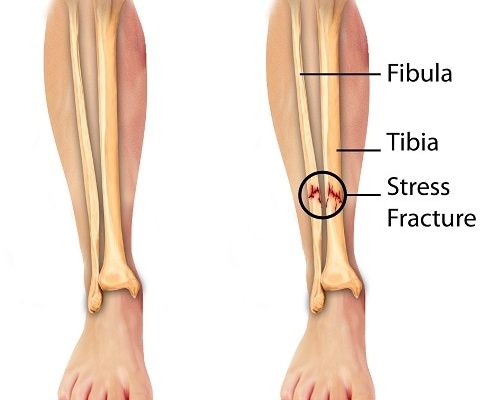

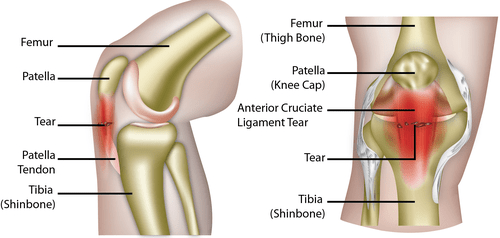

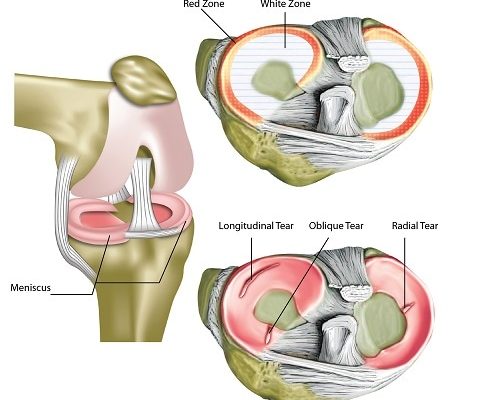

Diagnosis of groin strain is usually clinical, although imaging techniques can assist in eliminating other possibilities such as fractures. A thorough history should also be documented in order to make an accurate diagnosis.

In terms of imaging options, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the golden standard for confirming muscle strains, but ultrasound, bone scan, plain radiograph and computed tomography (CT) scanning can be used for differential diagnosis (that is, looking for other types of possible injuries that can present similar symptoms)3.

Like all muscle strains, groin strain injuries may be categorized in three broad categories depending on the nature and severity of the injury:

Grade I groin strains occur when there is a minimal loss in strength and function in the adductor muscles.

Grade II groin strains occur when there is a significant loss in the strength and function, but not a complete loss and the tissue is not fully ruptured.

Grade III groin strains occur when there is a complete rupture in the muscle tissue, resulting in the complete loss in muscle function.

Treatment

Few controlled studies have been conducted determine best treatment methods for adductor strains. Clinical experience, however, has shown that the RICE regimen (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) has a good recovery rate and help prevent further injury and inflammation. The high recurrence rate for these types of injuries may be due to incomplete rehabilitation or the inadequate time taken for recovery.

When appropriate, the next step is to restore range of motion and prevent the muscles from wasting away through strengthening exercises and groin strain stretches. The intensity should be gradually introduced until there is a pain-free full range of motion and at least 70% of the athlete’s original strength returns. At this point, the athlete may return to the sport.

For acute strains, this can take 1-2 months, while for chronic strains it may take up to 6 months for adequate recovery. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been used in treatment, but their efficacy is debatable and not supported by research literature2.

SOURCES

[1] Maffey, L., and Emery, C. (2007) What are the risk factors for groin strain injury in sport? A systematic review of the literature, Sports Med 37, 881-894.

[2] Morelli, V., and Smith, V. (2001) Groin injuries in athletes, Am Fam Physician 64, 1405-1414.

[3] Tyler, T. F., Silvers, H. J., Gerhardt, M. B., and Nicholas, S. J. (2010) Groin injuries in sports medicine, Sports Health 2, 231-236.