What is patellar tendinopathy?

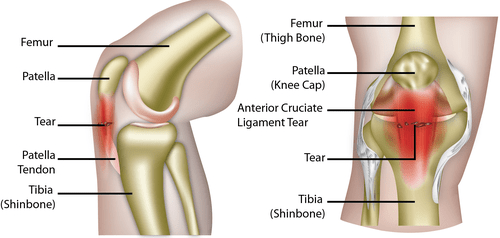

Patellar tendinopathy (also known as jumper’s knee or patellar tendonitis) is a soft tissue, overuse injury that affects the knee. It is usually a result of the area below the kneecap (patellar tendon) being over-stressed. Patellar tendinopathy is common in people who take part in active sports such as running, basketball, football and tennis sports.

What are the causes of patellar tendinopathy?

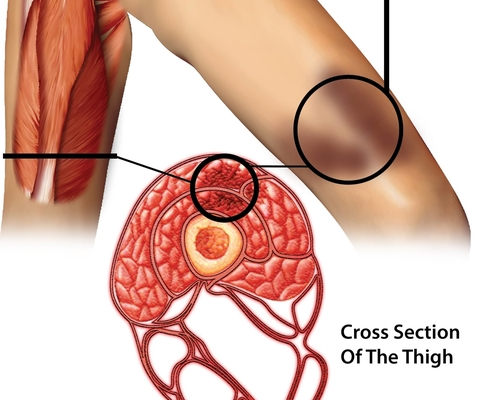

Patellar tendinopathy usually occurs in young athletes where regular strain on the patellar tendon occurs. Microscopic damage occurs in the patellar tendon due to the repeated bursts of jumping, landing and pivoting in certain sports. As the tendon tries to heal itself, it can become inflamed and painful.

What are the risk factors of patellar tendinopathy?

There are various things that can increase the likelihood of patellar tendinopathy, some of these include:

- Age

- Weight

- Flexibility

- Gender

Studies have shown that young people are more like to have this condition. Additionally, being overweight also increases the likelihood of developing patellar tendinopathy. It is found to be more common in men and those with limited flexibility around the quadriceps will be more prone to injuring their tendon.

Improper training practices as well as training for a prolonged period of time can also have an effect on the tendons in the knee. Common errors to avoid whilst training include:

- repetitive weight strain on the knee e.g. heavy squats

- high amounts of hill/distance running

- high amounts of plyometric exercises (activities that involve jumping)

What are the symptoms of patellar tendinopathy?

The most common symptoms of this condition include:

- sharp and aching pain just below the knee

- tenderness over the tendon

- inflammation of the tendon

- possible stiffness around the tendon at night and in the morning

The pain can also be aggravated by prolonged periods of sitting with varying degrees of pain depending on the level of the injury.

How is patellar tendinopathy diagnosed?

The diagnosis of ‘jumper’s knee’ is usually made by an examination of the person’s knee. Palpation of the knee is usually a reliable method for identifying patellar tendinopathy. In order to rule out other similar knee tendon disorders, an ultrasound (and in rare cases an MRI scan) would be carried out on the knee area.

Classifying patellar tendinopathy

This tendon injury can be classified in various stages, these include:

Stage 0 – No pain

Stage 1 – Pain only after intense sports activity, no undue functional impairment

Stage 2 – Pain before and after sports activity, you are still able to perform at a satisfactory level

Stage 3 – Pain during sports activity, it becomes increasingly difficult to perform at a satisfactory level

Stage 4 – Pain during sports activity, you are unable to participate in sport at a satisfactory level

Stage 5 – Constant pain preventing any participation in sporting activities

How do you treat patellar tendinopathy?

It is important that a person suffering from this injury does not return to sport or vigorous activities before the tendon has healed adequately.

Patellar tendinopathy can usually be treated in its early phases through a mixture of:

- rest of the affected knee(s)

- applying ice packs

- using anti-inflammatories or painkillers

- muscle strengthening

- stretching

- massage

- taping

What are the alternative treatments?

If a person is not responsive to the initial forms of treatment, then a health practitioner might utilise one or more of the following:

- high volume saline injection into the affected area

- GTN patches (glyceryl trinitrate)

- autologous blood injection – to help stimulate healing of the tendon

- surgery

There are multiple types of open surgical procedures that can be done on the knee tendon, the most common being an open excision of the affected area. The negative aspects of an open surgery are not related to the success rate but rather the amount of time needed for rehabilitation

Recent studies have also shown that steroid injections are not the best option at treating patellar tendinopathy. This is because of the increased risk of the tendon being weakened and even being ruptured as a result, which can lead to further long-term problems.

Eccentric Exercise Program

Rehabilitative exercise is usually recommended once adequate healing of the knee tendon is achieved. The NHS claims that the ‘eccentric exercise program‘ is the best method to fully recovering from this injury.

It is said that 7 out of 10 patients who undergo the rehabilitation program will be able to return to sporting activity within 3 to 6 months. This program should be supported by regular visits to a physiotherapist who will provide more professional support and guidance suited to what is required.

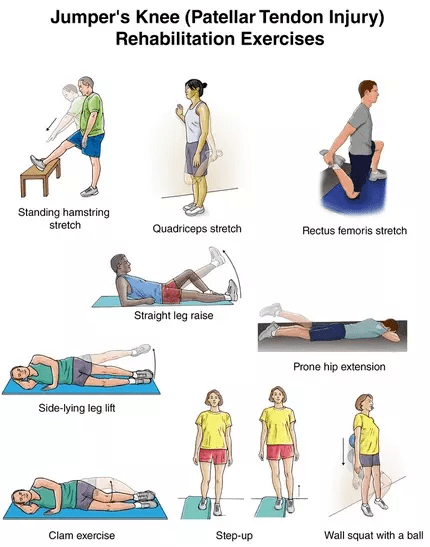

Some of the stretches that can help improve knee health, stability and tendon strength include:

- Standing hamstring stretch – with the affected leg on a raised stool, keep it straight and lean forward (bending at the hips). Hold for 15-30 seconds, repeat 1 or 2 times

- Quad stretch – stand on one leg next to a wall and pull from the ankle of the injured leg towards your buttocks. There should be a stretch felt in the quadricep and knee muscles, hold for 15-20 seconds.

- Rectus femoris stretch – kneel the injured knee on an exercise pad, if there is pain immediately, then it is not yet ready to exercise. Place the other leg on the floor (foot flat). Then gently grab and pull the ankle on the injured side towards the buttocks. Hold for 10-20 seconds, repeat 3-4 times.

- Straight Leg Raise – lying on your back with legs straight, bend the uninjured knee with the foot flat on the floor. Lift the injured leg about 5-8 inches off the ground and slowly lower, tightening the muscles in the thigh and keeping the leg straight. Repeat 10-15 times

- Side-lying Leg Lift – lying with legs straight, sideways on the uninjured side, lift the injured leg away from the body. Do this slowly for 10-15 repetitions.

- Prone Hip Extension – lie face down on your stomach with legs straight. With the arms resting under the head, raise the affected leg slowly above the floor, hold for 5 seconds then lower. Do this for 10-15 repetitions.

- Clam Exercise – lay on the uninjured side with hips and knees bent and feet together. Slowly raise the injured leg toward the ceiling while keeping the heels touching each other. Hold for 2 seconds and lower slowly. Repeat 10-15 times

- Step-up – stand with the foot of the injured leg on a raised step or platform keeping the other foot on the floor. Shift your weight onto the injured leg on the support, straightening it as the other leg comes off the floor, repeat this for 15-20 repetitions.

- Wall Squat with a Ball – with your back against a wall place a medium sized exercise ball or even a football behind your back. Keeping the back straight, slowly squat to a 45-degree angle, hold this for 10 seconds and then slowly slide back up the wall. Repeat 15 times.

FAQs

Q. How long does patellar tendonitis take to heal?

A. Depending on the severity of the injury, it can take between 3 – 9 months for recovery.

Q. What happens if patellar tendonitis is left untreated?

A. If left untreated, the condition can become chronic and get worse. This includes increased levels of pain, possible rupture of the tendon and an inability to partake in sports activities.

Q. Can I still run during my rehabilitation?

A. Although there might be an initial discomfort, there is small evidence that you will do further harm if you return to running. It is recommended however to refrain from running for at least the first month, as running too early might elongate the recovery process.

Q. Do patellar bands work?

A. Patellar bands are thin pressure bands wrong around the knee that help to reduce the pressure on the patellar tendon. Although these may help in reducing discomfort, they do not help to treat the underlying cause of the problem.

[trx_infobox style=”info” closeable=”no” bg_color=”#F9F9F9″ top=”inherit” bottom=”inherit” left=”inherit” right=”inherit”]SOURCES

[1] Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2015; 45(11):887-898.

[2] Lian ØB, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevalence of jumper’s knee among elite athletes from different sports: a cross-sectional study. Am J Sports Med. 2005; 33:561-567.

[3] Alexander RM. Energy-saving mechanisms in walking and running. J Exp Biol. 1991; 160:55-69.

[4] Cook JL, Khan KM, Kiss ZS, Coleman BD, Griffiths L. Asymptomatic hypoechoic regions on patellar tendon ultrasound: a 4-year clinical and ultrasound followup of 46 tendons. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001; 11:321-327.

[5] Malliaras P, Cook J, Ptasznik R, Thomas S. Prospective study of change in patellar tendon abnormality on imaging and pain over a volleyball season. Br J Sports Med. 2006; 40:272-274.

[6] Ferretti A, Papandrea P, Conteduca F. Knee injuries in volleyball. Sports Med. 1990; 10: 132-138.[/trx_infobox]