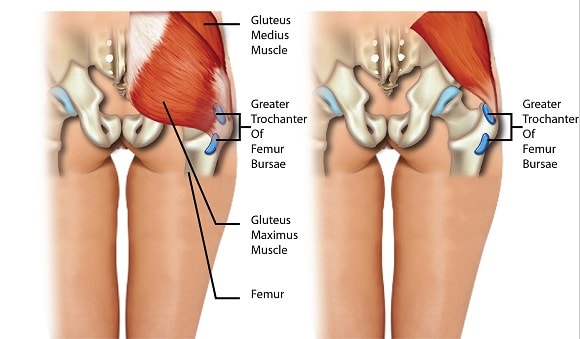

The greater trochanter is a projection in the upper head of the thighbone, near the hip joint, and is the site of attachment for five muscles. Around these bony protrusions and surrounding soft tissues are fluid-filled sacs called bursae, and these provide cushioning.

Trochanteric bursitis is a common condition of the hips that leads to pain in the outer (or lateral) hip, thigh, and buttocks. It’s a relatively common condition; however, its nature is poorly understood.

The suffix “-itis” implies that it is caused by inflammation, and this was widely believed to be the case, however recent scientific evidence has suggested that this is not the case. In fact, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have found that less than 10% of cases present inflammation of the bursae.

Although the exact mechanism of the disorder is not known, because current evidence shows lack of inflammation in majority of cases, the term trochanteric bursitis is also known as “greater trochanteric pain syndrome” or GTPS when describing lateral hip pain. The syndrome encompasses a wide range of causes, including muscle tears, tendinosis (chronic degeneration of tendons without inflammation) and other disorders.

In terms of prevalence, literature states that trochanteric bursitis affects approximately 1.8 to 5.6 patients per 1000 persons per year. Some papers state that its prevalence in the general population is 10 to 25%. It is typically present in middle aged adults, but its frequency in young adults is on the rise, particularly runners. It is also four times more frequent in women than in men in the general middle age population.

Symptoms

Symptoms of trochanteric bursitis include:

- Pain at the hip joint – Pain may be sharp at first, and then dull as time passes. The pain may be aggravated when sitting or lying down for a prolonged period of time, walking up a flight of stairs, sleeping on the affected side, running and climbing

- Difficulty walking

- Joint stiffness

- Joint swelling

- Warmth at the affected site

- A catching and clicking sensation

Causes/Risk Factors

Common risk factors of trochanteric bursitis are:

- Repetitive stress applied to the hip area, for example from running.

- Leg length discrepancy

- Infection and diseases that cause inflammation of the bursae (also called “true bursitis)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis for trochanteric bursitis is usually clinical, but can be complemented by the use of imaging techniques, especially when making differential diagnosis (that is, considering the possibility that the present symptoms may be due to a different injury). A thorough history is important and may reveal activities that causes overuse injuries.

The patient usually presents pain in the lateral hip, and tenderness at the greater trochanter when palpated (examined by touch). There is also pain at the extreme of hip rotation, adduction or abduction.

Pain can extend down to outer side of the buttocks and down the outer side of the thighs, but usually not beyond the proximal (upper) thigh. This feature can be used to differentiate between cases of trochanteric bursitis and other pathologies such as ITB disorders that usually causes pain below the knee.

Imaging techniques such as plain radiographs, ultrasounds, and MRI can greatly assist in making the correct diagnosis.

Treatment

Fortunately, trochanteric bursitis is usually resolved without any invasive treatment. Initial treatment usually involves non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ice, rest and activity modification (for example, avoiding stairs and reducing repetitive movements that aggravate the affected area). Patient may also be advised to sleep with a pillow between the knees to minimize bursae compression. Once the pain decreases, massages can also be introduced to aid in rehabilitation.

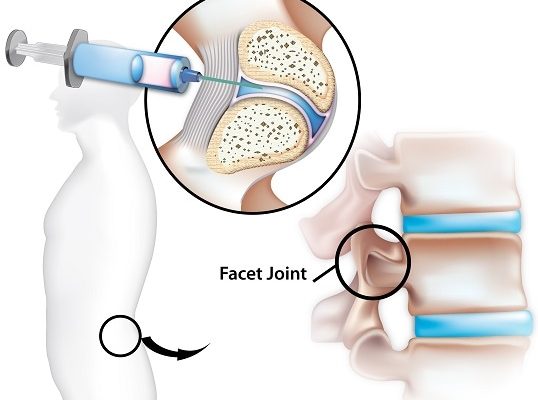

Weight loss and physiotherapy have also been added to many treatment regimens for trochanteric bursitis. If symptoms are unresponsive, corticosteroidal injections or local anaesthetics may be given, and these may also be given as a mixture. In most patients, a single injection has improved symptoms and drastically reduced pain. In some patients, however, multiple injections may be necessary.

If symptoms persist, surgery is considered. Surgical intervention has shown significant success for these patients, and has several options, the least invasive of which is endoscopy bursectomy. This technique has proven to be safe and has shown excellent results. The most invasive surgical option is an open osteotomy, which was traditionally the surgical choice, but with improvements in the less invasive endoscopic treatment, the latter is becoming more frequent.

[trx_infobox style=”info” closeable=”no” bg_color=”#F8F8F8″ top=”inherit” bottom=”inherit” left=”inherit” right=”inherit”]SOURCES

[1] Hugo, D., Jongh, H. R. d., and Anaest, D. (2012) Greater trochanteric pain syndrome, SA Orthopaedic Journal 11.

[2] Segal, N. A., Felson, D. T., Torner, J. C., Zhu, Y., Curtis, J. R., Niu, J., Nevitt, M. C., and Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study, G. (2007) Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: epidemiology and associated factors, Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88, 988-992.

[3] Dominguez, A., Seijas, R., Ares, O., Sallent, A., Cusco, X., and Cugat, R. (2015) Clinical outcomes of trochanteric syndrome endoscopically treated, Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135, 89-94.

[4] Domb, B. G., Lindner, D., Schwindel, L., Stake, C. E., and Bitar, Y. E. (2014) Outcomes of Endoscopic Treatment for Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: Minimum of Two Year Follow-Up, The Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2.

[5] Lustenberger, D. P., Ng, V. Y., Best, T. M., and Ellis, T. J. (2011) Efficacy of treatment of trochanteric bursitis: a systematic review, Clin J Sport Med 21, 447-453.[/trx_infobox]